11 Jan 2017

Why do your lymph glands swell up when you are sick?

Researchers from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute) have taken a big step in understanding why lymph nodes swell up during illness, and discovered that the process contributes to immunity against future infections.

Published in the prestigious journal Cell Reports, the research, led by University of Melbourne Associate Professor Scott Mueller, investigated the role of the cells that construct the lymph nodes, called stromal cells, during an immune response.

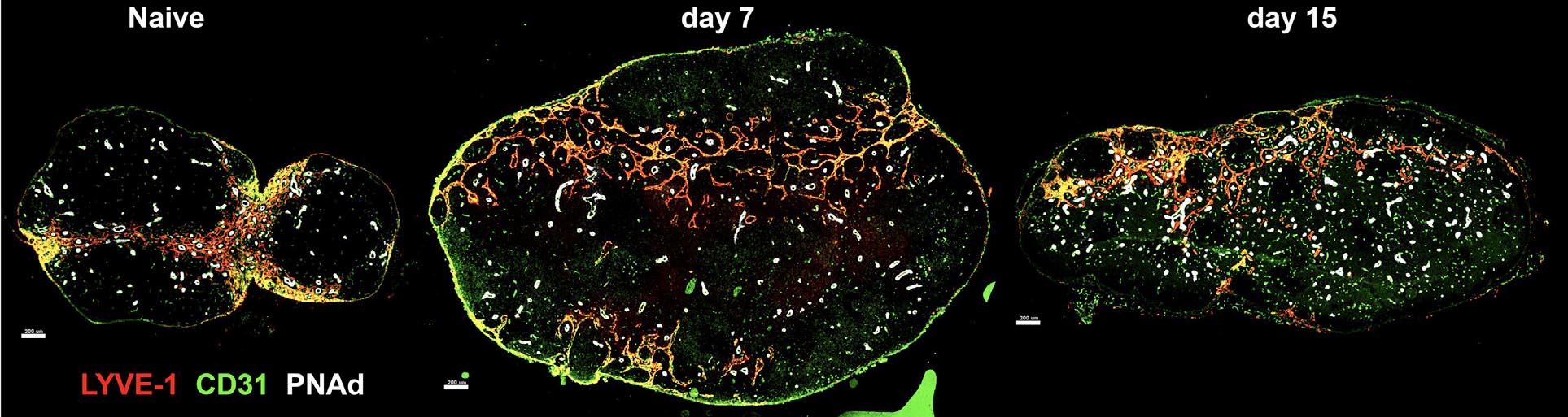

“We found that the stromal cells grow massively and change large numbers of genes. This supports the lymph node tissue to grow and mount an immune response to kill the infection or virus,” he said.

“The really surprising finding was that once the virus or infection was gone, the large numbers of genes that were expressed when the stromal cells grew returned to normal, but the tissue remained bigger and retained memory of the infection.

“It reorganised itself and stayed larger so if the infection returns, it doesn’t need to work as hard to fight, it responds quicker and better, contributing to immunity.”

Associate Professor Mueller and his team tested stromal cells with herpes simplex virus, the smallpox vaccine and a mouse virus, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus.

“Because infections and some cancers cause swollen lymph nodes, it’s crucial to understand the role they play in immunity,” he explained.

“We now know that many different genes change their expression in stromal cells in the lymph nodes during infection, and this information will be important for new research into what these genes are and what they do, which could be used as new targets for therapies to either improve or reduce the immune response.”

Associate Professor Mueller added that in the instance of HIV, the virus significantly damages stromal cells, so further knowledge of their function might have implications for treatment.

This research was conducted in collaboration with The University of Melbourne, the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Yamaguchi University Graduate School of Medicine, Japan, and the Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, Japan.