When a pathogen hits our immune system, it triggers a rapid chain reaction that causes protective immune cells to spring into action. However, some pathogens are good at staying under the radar and only send weak signals that fail to fully alert the immune system to their presence. In these cases, the immune detection system needs an additional signal to get the process going properly, much like adding kindling to a spluttering fire.

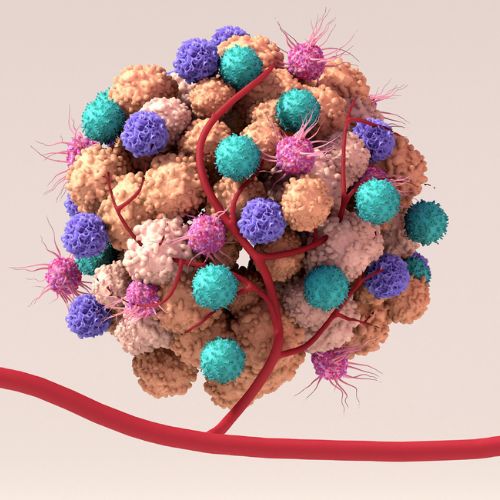

Our research group studies how pathogens are recognised by immune cells, and the cellular communication network that leads to effective and long-lasting protective responses. We particularly focus on how different pathogens trigger differing signals that influence the activation and responses of key immune players; the decision-makers, called dendritic cells, and the actioners, the killer T cells (CD8+ T cells).

Ultimately, understanding how we can manipulate these early signals can improve the formation of long-lasting “memory” killer T cells that permanently reside in tissues and provide front-line defence for when repeat infection occurs.

In our recent study published in Nature Immunology we looked carefully at how the immune response is trained by vaccination, specifically a live-attenuated version of the malaria-causing parasite, Plasmodium (radiation-attenuated sporozoites (RAS)). In this setting, the decision-making dendritic cells activate killer T cells, thereby training the system for long-term protection against malaria.

We discovered that a specialised set of T cells (gd T cells) provide a key signal that kick starts the response to the parasites. If the gd T cells aren’t present, or if they can’t provide the key signal, then the entire response fails, that is long-lasting protection fails to form leaving the immune system untrained and vulnerable to malaria infection.

The molecule produced – the so-called signal – is the cytokine interleukin-4 (IL-4). This was a particularly unexpected finding because gd T cells are rarely reported to produce this signal, and because IL-4 is normally considered to induce a very different immune response to the one that is needed to control malaria infection.

In our study, we showed that when Plasmodium sporozoites are injected into mice, IL-4 allows both killer T cells and dendritic cells to reach their full potential, ensuring that the ‘spluttering fire’ is kept alight. To dissect the effects of IL-4, we developed a novel CRISPR gene knockout system in dendritic cells taken directly from the spleen, allowing us to specifically test the function of genes in these cells.

Through a collaboration with researchers at the Burnet Institute, we were also able to show that people in Indonesia with active malaria infection had more gd T cells that produced the key signal, IL-4, when compared to people from the same area that did not have active infection.

Our findings are the first to describe gd T cell-derived IL-4 playing a role in boosting the cellular immune response to an infection.

By shedding light on a previously underappreciated role for IL-4-derived from gd T cells, our work points to new ways of strengthening killer T cell-based vaccines and immunotherapies when immune signals are weak.