A new approach developed by a team led by the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute) can flag emerging Buruli ulcer hotspots two to six years before human infections occur, using possum excreta surveillance and cutting-edge genomics. The findings mark an important advance in early warning for this debilitating skin disease spreading across Victoria.

Buruli ulcer, a serious skin infection caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium ulcerans, has a long and variable incubation period, making it difficult to pinpoint where patients were exposed. Although considered a neglected tropical disease, Victoria continues to see rising incidence and geographic spread.

Dr Finn Romanes, Director of the Western Public Health Unit in Victoria, said that, for example, there are now twelve suburbs in Melbourne’s west where people are at risk of Buruli ulcer.

“This year alone, notifications have increased by 40 per cent in the western suburbs, with 114 cases recorded so far in 2025, up from 82 in 2024,” said Dr Romanes.

Recent research led by the Doherty Institute confirmed that, in Australia, mosquitoes transmit M. ulcerans to humans (Mee , Buultjens et al, 2024), and that native possums can also get Buruli ulcer and shed the bacteria in their excreta (Vandelannoote et al, 2023).

Focusing on Melbourne’s inner northwest suburbs (Brunswick West, Pascoe Vale South, Essendon, Moonee Ponds and Strathmore) and the Geelong suburb of Belmont, researchers analysed M. ulcerans DNA in possum excreta and compared it with bacterial DNA from human cases to determine whether infections were locally acquired.

“We know possums have very small home ranges, so the presence of M. ulcerans in their excreta is a highly reliable indicator that the bacterium is present locally,” said the University of Melbourne’s Dr Andrew Buultjens, Senior Research Fellow at the Doherty Institute and first author of the recent paper published in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

“By using DNA sequencing to compare bacterial genomes from possum-derived and human-derived M. ulcerans, we found that clusters of positive possum samples closely matched the locations of human cases. This clear spatial overlap confirms that transmission in both Melbourne’s inner northwest and Geelong is occurring locally.”

Using advanced genomics modelling, the team also estimated that M. ulcerans was introduced to these areas two to six years before the first human cases appeared locally.

“This research shows we don’t have to wait for people to become infected before we know an area is at risk,” said the University of Melbourne’s Professor Tim Stinear, Director of the WHO Collaborating Centre for Mycobacterium ulcerans at the Doherty Institute and lead author of the study.

“Forewarned is forearmed,” said Professor Stinear.

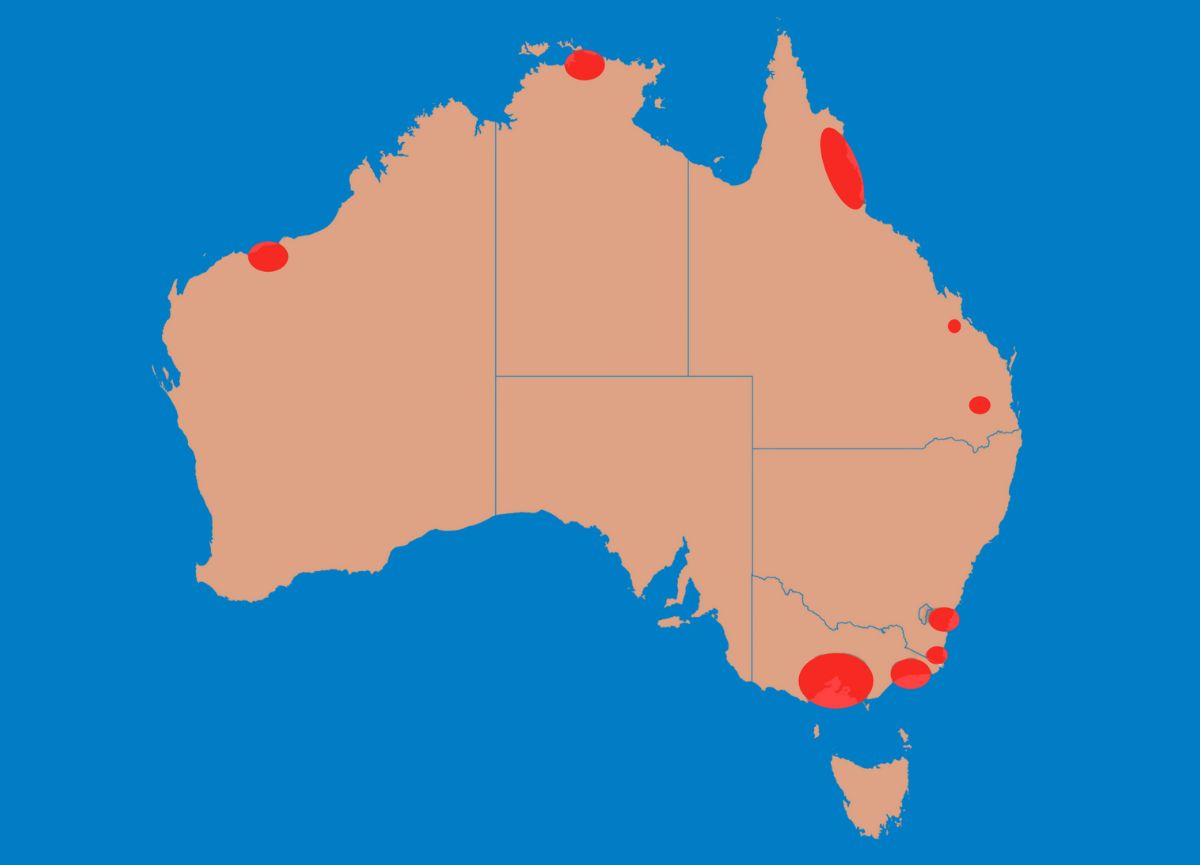

“Our method, combining environmental surveillance and genomic fingerprinting, allows us to identify emerging hotspots early. As Buruli ulcer continues to expand into new areas, it offers a scalable, proactive model to protect communities, to protect wildlife and to guide early public health interventions in other affected regions.

“This early warning system provides critical knowledge for targeted public health measures, such as community messaging and alerting local clinicians, to reduce exposure and ensure timely diagnosis and treatment.”

This integrated approach – linking wildlife, environment and human health – is a striking example of One Health in action. By better understanding possum populations and the bacteria they shed, scientists can now map future Buruli ulcer hotspots with unprecedented precision.

Dr Romanes said now is the time to take preventive action.

“With mosquitoes confirmed as the vector in Australia, people can protect themselves by using repellents, wearing long sleeves and avoiding mosquito bites in these hotspots,” said Dr Romanes.

“Mosquito numbers usually surge from November to April, and most people then develop a Buruli ulcer lesion four to five months later. GPs can diagnose the infection with a simple skin test.”

Further information can be found at:

https://www.wphu.org.au/health-topics/buruli-ulcer/

https://www.health.vic.gov.au/infectious-diseases/mycobacterium-ulcerans-infection

Peer-review: Buultjens A et al. Defining new Buruli ulcer endemic areas in urban southeastern Australia using bacterial genomics-informed possum excreta surveys. Applied and Environmental Microbiology Journal (2025). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01602-25

Collaboration: This work is the result of a collaborative effort between the Doherty Institute, Melbourne Veterinary School at the University of Melbourne, the Western Public Health Unit and the Victorian Department of Health.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Victorian Department of Health.

More updates and news from the Doherty Institute