Researchers at the Doherty Institute have discovered that Mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells, a specialised subset of immune cells best known for fighting bacterial infections, exist as a tissue resident population of cells in the brain, where they may help to combat brain tumours, such as glioblastoma.

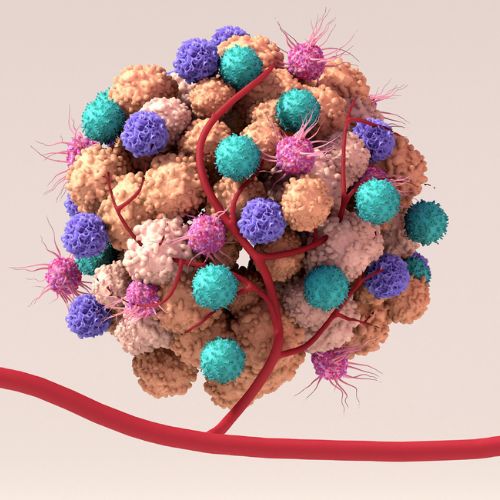

Glioblastoma, a fast-growing and aggressive brain tumour, is the most common primary brain tumour in adults. Life expectancy is limited, with most patients surviving only 12-15 months after diagnosis.

While immune therapies, such as CAR-T cells – where a patient’s own immune cells are modified to fight cancer, have radically transformed treatment for many cancers, brain tumours remain a challenge. There is an urgent need to understand how the immune system interacts with tumour cells in the brain to develop new therapies for brain cancer.

A study published in Neurology: Neuroimmunology and Neuroinflammation, led by Doherty Institute researchers Professor Alexandra Corbett and Dr Alexander Barrow, provides new insights into immune cell surveillance of the brain.

Using publicly available datasets from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), researchers tested whether having more MAIT cells was an important factor in survival for glioma patients.

The University of Melbourne’s Dr Alex Barrow, a Laboratory Head at the Doherty Institute and co-senior author, said the findings suggest that MAIT cell activation, rather than simply presence, is key for immune surveillance.

“Surprisingly, we found that only activated, but not resting, MAIT cells were associated with better outcomes in patients with gliomas,” said Dr Barrow.

“This was our first indication that activating MAIT cell functions may be important for immune surveillance of the brain.”

Mouse studies in collaboration with Davide Moi, Dr Roberta Mazzieri and Professor Riccardo Dolcetti, at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre (Peter Mac), revealed that MAIT cells, unlike conventional T cells, are predominantly tissue-resident in the brain and can infiltrate brain tumours.

Intriguingly, mice genetically deficient in MAIT cells succumbed to brain tumours more rapidly than normal mice, suggesting a protective role for MAIT cells. Protocols previously developed to boost and activate MAIT cells in circulation and other organs, were also effective in boosting MAIT cells in the brain, suggesting a potential to harness MAIT cells for immunotherapy. Interestingly, in mice with boosted MAIT cells, the functions of these cells appeared to be dampened inside the tumours.

The University of Melbourne’s Dr Eleanor Eddy, Research Officer at the Doherty Institute and first author of the paper, said the results open promising new therapeutic angles.

“It’s clear from our results that MAIT cells have a helpful, rather than harmful, presence in the context of brain tumours. They act like vigilant sentinels in the brain, helping to keep tumours in check,” said Dr Eddy.

“Whether we can take this further is an exciting question to ponder; it appears that while we can successfully boost MAIT cells in the brain, there’s another missing piece of the puzzle to unlock their anti-tumour functions.”

The University of Melbourne’s Professor Alexandra Corbett, Laboratory Head at the Doherty Institute and co-senior author, said these findings lay the groundwork for future research into MAIT cells as potential tools in brain cancer treatment.

“We are only beginning to understand the complex interactions of immune cells in the brain,” said Professor Corbett.

“Our research reveals previously unknown roles for MAIT cells in normal brain function and highlights exciting potential to explore how modulating MAIT cell activity could be used in immune therapies, as well as intriguing genetic links between the brain and MR1, a key molecule that activates MAIT cells.”