By Dr Thomas Burn, Research Officer in the Professor Laura Mackay Laboratory at the Doherty Institute

By Dr Thomas Burn, Research Officer in the Professor Laura Mackay Laboratory at the Doherty Institute

Even with this built-in protection, the immune system does not always win, and cancer touches almost everyone in some way, through our own experience or that of people we love.

One reason killer T cells fail is that tumours fight back. Tumours can wear the killer T cells down over time and trigger the expression of molecular ‘brakes’ that dampen their activity. This worn-out state is called T cell ‘exhaustion’.

Over the past two decades, scientists have developed successful cancer immunotherapies that release these brakes, allowing exhausted T cells to gain a second wind as they try to attack tumours.

This work was recognised with the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2018.

Despite the success of these treatments, they do not work for every patient or every cancer and can lose effectiveness over time. Understanding why remains a critical next step if we want to make immunotherapy work for more people, more reliably.

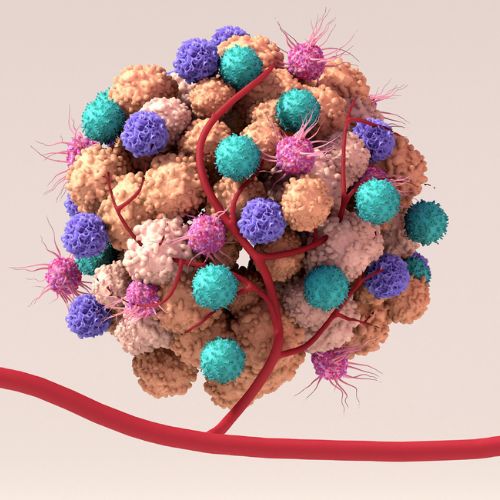

In our Nature Immunology study, also featured on the journal’s cover we identified two distinct groups of killer T cells in many cancer types.

The first are exhausted T cells. The second are tissue-resident memory T cells, referred to as “TRM cells”. On the surface, exhausted and TRM cells can look very similar, which means they have been grouped into the same bucket in previous studies.

We combined advanced sequencing, spatial imaging, and functional testing of these killer T cells from human cancers to pinpoint the key differences between these cell types.

We found that the TRM cells were more functional and were linked with improved survival in breast cancer. But TRM cells were not the cells that responded to current immunotherapies, which mainly act on exhausted T cells.

The key insight was that killer T cell fate was driven by what the T cells recognise. Killer T cells are highly specific and need to recognise ‘tags’ on cells, much like one key fits into only one lock. Exhausted T cells became exhausted because they were recognising tumour tags repeatedly.

TRM cells, in contrast, were often physically separated from tumour cells, or were not tumour specific at all. Many were in fact ‘bystanders’, specific for past infections such as the flu, or COVID-19.

This matters because in many cancers, most of the killer T cells present are TRM cells. These cells can be highly capable, yet current treatments are not designed to deliberately engage them. Finding ways to bring bystander TRM cells into the fight will improve responses and expand the number of cancers and patients that benefit from immunotherapy.

Peer-review: Burn T et al. Antigen reactivity defines tissue-resident memory and exhausted T cells in tumors. Nature Immunology (2025). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-025-02347-9

Collaboration: This work is the result of a collaborative effort between the Doherty Institute, Austin Health, Harvard Medical School (US), La Trobe University, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Pfizer Inc, University of Pennsylvania (US), WEHI and the University of Western Australia

Funding: This research was supported by the Cancer Council Victoria Grants-in-Aid, Pfizer Inc., National Health and Medical Research Council and the National Institutes of Health

More updates and news from the Doherty Institute